James Halliday's Top 100 considers all corners of wine – from styles, to movements, and issues faced by grape-growers and winemakers daily. As tradition follows, The Top 100 is published in The Weekend Australian Magazine and online at Wine Companion.

Below precedes James’ Top 100 Wines of 2018, highlighting the conditions of the industry over the past year.

The state of play: exports

There is a plethora of statistics that are bound to come up in any discussion of the June ‘18 financial year, but one stands out. Australia’s exports to China are equal to that of its next three largest markets combined: the US $424 million, UK $384 million, and Canada $199 million.

Too many eggs in the one basket? There is plenty for the doomsayers to feed on. The compound annual growth rate of exports to China for the five years ending 30 June 2018 was 32% by value and 34% by volume. Impressive? Yes and no. The increase for last year (June ’18) was 66.1% by value and 50.3% by volume. This for a market that amounted to $1 million for the 2000 financial year, and $1.12 billion (including Hong Kong and Macau) for this year. How long can the boom last?

It’s the only one of our major export markets not to have English as its mother tongue, and not to have a free market (actual or theoretical) system. But it is now accepted that most of the imported wine is being consumed, in contrast to the fears of the early years of stock being caught in a labyrinthine supply chain and/or turn-table gift-giving.

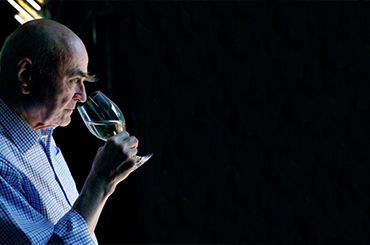

No one should doubt the intelligence of the Chinese people and their thirst for knowledge. But using book knowledge about the quality and style of a given wine is no substitute for tasting it, the more carefully, the better. The marriage of Cantonese steamed fish and a full-bodied shiraz or cabernet sauvignon tells you there are shortcomings in understanding. As does the much-enjoyed endless consumption of small glasses of red wine drained in a single swallow at a restaurant or private room with no thought of (attempting to) assess the bouquet, instead just a rush to re-fill the glass. At least the addition of Coca Cola is in retreat.

So what are the positives driving this growth and its sustainability? The spend on alcohol in China in 2017 was $397 billion, of which $193 billion was spirits (Moutai and other local or imported brands); $110 billion was beer; and $93 billion was wine. Wine comprised $68 billion still wine, $24 billion rice wine, and $0.7 billion sparkling wine. Australia’s $1.12 billion puts it in second place behind France (closing the gap fast), leaving Australia with space to grow even if the total market stays unchanged.

But it won’t. Today’s young Chinese, highly mobile and who now constitute the major part of the number of inbound visitors to this country, are being exposed to wine in a way their parents and grandparents couldn’t have even envisaged. Sixty years ago, when I was at Sydney University approaching the end of my Arts Law degree, fortified wine accounted for 90%-plus consumption (detailed statistics weren’t published of wine sales), table wine 10%. Those of us residents of the university’s St Paul’s College who drank table wine were allowed to have it in the Great Hall for dinner on Wednesday night and weekends. Our regular drink was beer, and lots of it.

In the super heated movement of all things in China, sales of Australian wine is growing rapidly. Wine Intelligence, the leading worldwide wine research business, says that Australia has the second highest brand awareness and consumption levels (after France) of urban upper-middle class imported wine drinkers. Moreover, 36% have drunk Australian wine in the past six months. As an aside, Wine Intelligence reports that three wines have the highest Brand Power: Chateau Lafite, Yellow Tail and Penfolds, the last with the highest Connection Index.

Australian visitors to China will understand why 45% of consumers buy wine online. They can research its background, compare prices and chat about it without any fear of embarrassment, but also have the wine delivered to them.

The winds of change are most obvious in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities, but there are 100 cities with a population of over one million, online marketing creating brand awareness and sales at a more rapid rate than department stores, let alone small specialist retailers.

President Xi Jinping is moving to develop those parts of western China that have so far fallen outside the economic transformation of the eastern half. The cumulative demand will continue to increase, and the question is which countries will be able to supply it. The answer isn’t easy to calculate. Chile casts the longest shadow, but (subject to aberrant weather) traditional European markets will also happily join the party. Italy, the south of France, South Africa and Western Europe will all be offering to help.

So will Australia’s medium to large scale producers re-allocate some of the amount of wine that would normally be sold on the domestic market and earmark it for export to China? China pays more per litre for our wine than other significant markets, so they, too, may find less wine available. How many eggs should be moved to China?

What’s happening at home?

Australia’s 2018 vintage produced 1.79 million tonnes, 10% lower than the record 2017 vintage, and only a whisker above the 10-year average 2008-2017 of 1.76 million. The reason for the lowest crush since 2015 was the dry winter, and a reaction after the record ’17 crush. So there was no significant planting, and there has been a dry autumn, winter and spring in eastern Australia leading into the ’19 vintage.

As things stand now, all red wines are experiencing substantially greater demand than supply, white wines on the cusp, with a stretched supply. The drought continues; soil measure levels across South Eastern Australia are critically low. Those vineyards with irrigation water will face critical decisions on use now and through to vintage.

Those responsible for sales will have to tread very lightly. It’s a global world, with no place to hide, so if the next six months unfold as seems most likely, decisions will have to be taken on the short or medium term. Can you persuade your best markets other than China to line up for lesser supply from the ’18 and ’19 vintages, keeping second level markets happy enough to take less wine than they had expected?

The domestic market and the 80 table wines selected

What was the outcome for the prices of the 80 still table wines selected for the Top 100? Nine were priced between $100 and $500; 20 wines between $50 and $99, and another 15 between $30 and $49 each. Given that for various reasons (none concerned with quality or value for money) the two most expensive wines on the market (Grange and Hill of Grace) weren’t chosen, the weighted average price would have been even higher.

It appears that both supply and demand are operating to lift prices, and will continue to do so over the medium term future. Behind these local forces, prices of top French wines are surging with unprecedented speed. The prices of the newly arriving red Burgundies are eye-watering. Here, too, the China factor is in play, forcing pinot lovers to balance their spend with a mix of imported and local wines, and to do so across all red wines.

The mastadon in the room

Economists looking at rising standards of living amongst all the Asian economies say there is an emerging middle class with disposable income that is likely to duplicate that of China. India is most frequently discussed, but the whole swathe encompasses Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. All are buying more wine than ever before.