Thanks to its ability to withstand dry, hot conditions, Sicily’s nero d’Avola is being embraced by Australian vignerons, who’ve found that this medium-bodied red has a natural affinity with our warmest wine regions.

If you were the Willy Wonka of viticulture and could invent the perfect wine variety, you would need to consider many things – not least how it tastes. You would need to create a variety that was well suited to particular climates so it didn’t strain resources. It would also need to be well behaved in the winery so it could provide great wine often and be attractive to drinkers across a range of occasions. You would also want it to be great with food as well as on its own and, most importantly, be a delicious drink with the capacity for complexity and evolution.

If you could invent a variety for Australia right now, you would probably make a red wine that could endure Australia’s sometimes challenging climate. It would probably also be medium-bodied to reflect the shift towards lighter red wines and perhaps have some Italian pedigree because that style is on the rise. If you could invent such a thing, you might make something like nero d’Avola. You might, except the variety already exists and has been around for more than 500 years. Lucky for you, it is now being made in Australia.

Although nero d’Avola is a delicious wine to drink (more on that later), one of the greatest appeals for growing it here is its suitability to dry, arid climates. This is particularly relevant as the Australian wine industry predicts and prepares for the effects of climate change. One strategy has been to plant varieties that are best suited to the climatic traditions. Many of Australia’s wine regions were established with grape varieties sourced from temperate growing regions of France, but some of Australia’s wine regions have a distinctly warm climate, making them better suited to the Mediterranean, Spanish and southern Italian varieties.

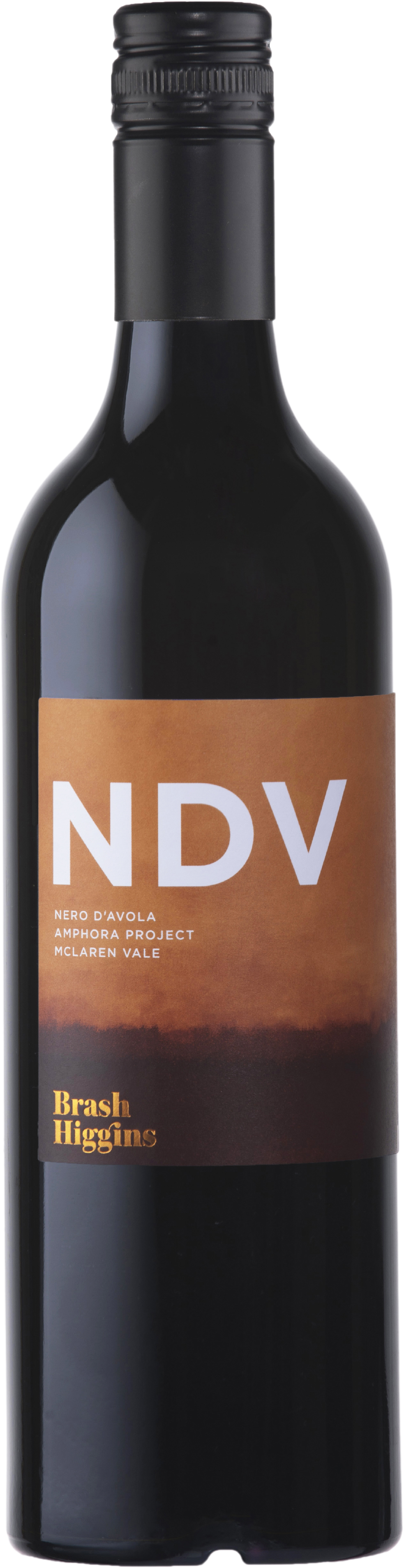

Ashley Ratcliff is a viticulturalist in South Australia’s Riverland region that some climate change experts speculate might one day be too warm to sustain viticulture. Seven years ago, Ashley planted nero d’Avola cuttings from the Chalmers vineyard in his Ricca Terra vineyard, which specialises in southern Italian varieties. After a few vintages, he has gotten to know the variety. “It can be difficult and is a loaded gun in the wrong hands,” he says. “If you are looking to plant something where it’s going to get hotter and there’s going to be less water, it’s a great variety.” Brad Hickey, winemaker and owner of McLaren Vale wine label Brash Higgins, made his first nero in 2011 using beeswax-lined clay amphorae. He also cites climatic suitability behind his reasons for seeking out the variety. “When I first moved to McLaren Vale in 2007, South Australia was in a drought. The next two years were just as bad,” he says. For Brad, the decision to plant nero d’avola in the Vale was easy, particularly as he has a background in horticulture. “It is taught you should transplant plants into climates that are similar to those they are native to. McLaren Vale and Sicily are so similar, both climatically and geologically, that nero d’Avola made perfect sense.”

Brad organised a recent tasting of 12 Australian and 20 Italian nero d’Avolas in Melbourne. The line-up showed the variety and diversity of available flavours and styles. Where the Italian wines showed the breadth of wines – from big, heavy and structured to softer styles – the Australian wines were lighter, prettier and more floral. They reflected the youthful vine age; remember, it was not released here until 2001 and took several years after for the vineyards to bear fruit – as much as the winemaking hand has taken time to master it. Overall, the Australian wines showed the potential of these vineyards, with more vine age and greater knowledge and experience, to produce a range of new and exciting wines.

It’s not only the diversity across the wines in the glass that makes nero so exciting, but also the way it holds up compared to other red wines. For Brad Hickey, the variety’s ability to make a counterpoint to the fuller-bodied styles planted in the McLaren Vale region is important. “That great acidity in nero means we can make a lighter-style red from it, which also offers diversity in our region, allowing for lighter range on the red spectrum compared to the fullerbodied styles the Vale does so well.” Another of the wine’s great attractions is that it pairs so well with food. “The absence of oak and its high natural acidity makes it a dream to pair with rich, braised dishes, and also lighter grilled fish and white meat,” Brad says. “It matches well with spicy food, including Indian and Szechuan, and classic Mediterranean dishes such as seared tuna with nicoise olives and capers. It’s a great all-round red.”

Brad Wehr agrees. “The lighter styles of nero make for simple, flavoursome lunch wines, or for evening barbecues, but they can actually handle more than that.” As well as being such a good food wine, it is also great on its own and, as Brad says, it’s a wine that can be lightly chilled on a hot day.

Aromas include bright red fruits – think cherries, redcurrant, pomegranates and strawberries – as well as savoury notes, such as roast tomatoes, baked quince, rhubarb and dried herbs. More exotic versions feature floral elements, including dried rose petals, and all have a dash of exotic sweet spices, as well as naturally high acid and generous tannins. Mostly, nero d’Avola produces a medium-bodied wine. Its great strengths are that it offers lovely red fruits, but with a savoury edge, meaning it’s an excellent wine to have with food or on its own.

If you were the Willy Wonka of viticulture and could invent the perfect wine variety, you would need to consider many things – not least how it tastes. You would need to create a variety that was well suited to particular climates so it didn’t strain resources. It would also need to be well behaved in the winery so it could provide great wine often and be attractive to drinkers across a range of occasions. You would also want it to be great with food as well as on its own and, most importantly, be a delicious drink with the capacity for complexity and evolution.

If you could invent a variety for Australia right now, you would probably make a red wine that could endure Australia’s sometimes challenging climate. It would probably also be medium-bodied to reflect the shift towards lighter red wines and perhaps have some Italian pedigree because that style is on the rise. If you could invent such a thing, you might make something like nero d’Avola. You might, except the variety already exists and has been around for more than 500 years. Lucky for you, it is now being made in Australia.

Go to section: In the vineyard | Diversity and flavour | A wine discovery | Florals and spice | Nero d'Avola at a glance

In the vineyard

Nero d’Avola is native to Sicily, where it’s the region’s most planted variety. In recent years, plantings have spread to other parts of the world, including Australia, where the Chalmers family nursery imported the first nero d’Avola vines in 1998 (although not released from quarantine for cultivation until 2001). Today, there are more than 55 nero d’Avola vineyards in Australia.Although nero d’Avola is a delicious wine to drink (more on that later), one of the greatest appeals for growing it here is its suitability to dry, arid climates. This is particularly relevant as the Australian wine industry predicts and prepares for the effects of climate change. One strategy has been to plant varieties that are best suited to the climatic traditions. Many of Australia’s wine regions were established with grape varieties sourced from temperate growing regions of France, but some of Australia’s wine regions have a distinctly warm climate, making them better suited to the Mediterranean, Spanish and southern Italian varieties.

Ashley Ratcliff is a viticulturalist in South Australia’s Riverland region that some climate change experts speculate might one day be too warm to sustain viticulture. Seven years ago, Ashley planted nero d’Avola cuttings from the Chalmers vineyard in his Ricca Terra vineyard, which specialises in southern Italian varieties. After a few vintages, he has gotten to know the variety. “It can be difficult and is a loaded gun in the wrong hands,” he says. “If you are looking to plant something where it’s going to get hotter and there’s going to be less water, it’s a great variety.” Brad Hickey, winemaker and owner of McLaren Vale wine label Brash Higgins, made his first nero in 2011 using beeswax-lined clay amphorae. He also cites climatic suitability behind his reasons for seeking out the variety. “When I first moved to McLaren Vale in 2007, South Australia was in a drought. The next two years were just as bad,” he says. For Brad, the decision to plant nero d’avola in the Vale was easy, particularly as he has a background in horticulture. “It is taught you should transplant plants into climates that are similar to those they are native to. McLaren Vale and Sicily are so similar, both climatically and geologically, that nero d’Avola made perfect sense.”

Diversity and flavour

As a wine, nero d’Avola has a lot to offer. “It’s a near-perfect variety,” says Brad Wehr of Amato Vino, who has been making a nero d’Avola from Ashley’s Riverland vineyard. “The nose can be pretty, floral and spicy, yet earthy and meaty with lots of red fruits. The flavours on the palate cover the spectrum, from mouth-filling, red-fruited juiciness and eastern spices, through to dried herb, savouriness and crunchy acidity.”Brad organised a recent tasting of 12 Australian and 20 Italian nero d’Avolas in Melbourne. The line-up showed the variety and diversity of available flavours and styles. Where the Italian wines showed the breadth of wines – from big, heavy and structured to softer styles – the Australian wines were lighter, prettier and more floral. They reflected the youthful vine age; remember, it was not released here until 2001 and took several years after for the vineyards to bear fruit – as much as the winemaking hand has taken time to master it. Overall, the Australian wines showed the potential of these vineyards, with more vine age and greater knowledge and experience, to produce a range of new and exciting wines.

It’s not only the diversity across the wines in the glass that makes nero so exciting, but also the way it holds up compared to other red wines. For Brad Hickey, the variety’s ability to make a counterpoint to the fuller-bodied styles planted in the McLaren Vale region is important. “That great acidity in nero means we can make a lighter-style red from it, which also offers diversity in our region, allowing for lighter range on the red spectrum compared to the fullerbodied styles the Vale does so well.” Another of the wine’s great attractions is that it pairs so well with food. “The absence of oak and its high natural acidity makes it a dream to pair with rich, braised dishes, and also lighter grilled fish and white meat,” Brad says. “It matches well with spicy food, including Indian and Szechuan, and classic Mediterranean dishes such as seared tuna with nicoise olives and capers. It’s a great all-round red.”

Brad Wehr agrees. “The lighter styles of nero make for simple, flavoursome lunch wines, or for evening barbecues, but they can actually handle more than that.” As well as being such a good food wine, it is also great on its own and, as Brad says, it’s a wine that can be lightly chilled on a hot day.

A wine discovery

Retailer Paul Ghaie, who owns and runs boutique Melbourne wine store Blackhearts & Sparrows with his sister Jessica, stocks six nero d’Avolas priced between $15 and $35. Paul says nero is an ideal wine to introduce people to Italian varieties. “Italian wine styles can be a bit hard to grasp for some drinkers due to their extremely structural and savoury nature,” Paul says. “Nero d’Avola counters this by offering great drinkability; a silky, rich, dark fruit spectrum that is at once familiar and beguiling, yet exotic enough to lift it into the realm of new discovery.” It’s exciting to find a wine that ticks all these boxes and, by all accounts, it has immense potential in Australia. As Brad Hickey puts it, “The story of nero d’Avola sparks the imagination of wine drinkers, which is beautiful and prompts them to go on a journey to try something different.”Florals and spice and all things nice

The flavour spectrum of nero d’Avola varies depending on where it is grown, how old the vines are and how it is made. When grown in sandy sites (like lower parts of Sicily and Mildura), the wines are lifted, floral, delicate and more perfumed, while those from more elevated sites produce heavier, structured and more robust wines.Aromas include bright red fruits – think cherries, redcurrant, pomegranates and strawberries – as well as savoury notes, such as roast tomatoes, baked quince, rhubarb and dried herbs. More exotic versions feature floral elements, including dried rose petals, and all have a dash of exotic sweet spices, as well as naturally high acid and generous tannins. Mostly, nero d’Avola produces a medium-bodied wine. Its great strengths are that it offers lovely red fruits, but with a savoury edge, meaning it’s an excellent wine to have with food or on its own.